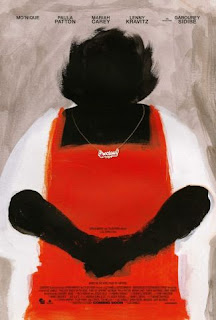

Film Review #215: Precious

Film Review #215: Precious2009

Director: Lee Daniels

Cast: Gabourey Sidibe, Mo'Nique, Paula Patton, Lenny Kravitz

Several weeks ago an irate letter-writer worried in The Post-Standard that Syracuse might miss Precious altogether. Although that letter actually appeared the morning after Nat Tobin announced on his weekly e-list that he was bringing Precious to Manlius Art Cinema, there was a lag before Regal Theaters booked the film into Carousel. It took breaking all sorts of attendance records in the very limited initial theatrical release that Precious got from Lionsgate Films for the mall chains – here and in 100 markets nationwide – to get wind of its profitability. Precious – based, as its longer official title tells us, on the 1996 novel Push by Sapphire – opened last Friday at both Manlius and Carousel Mall, and it was satisfying to see some weekend showings sold out.

The first film ever to win the Audience Award at both the Sundance and Toronto film festivals, Precious is the second feature film directed by Lee Daniels, who has mainly worked as a producer on edgy films like Monster’s Ball. Set in 1987, the film tells the story of teen-aged Claireece “Precious” Jones (Gabourey Sidibe), her sexual and physical abuse at the hands of both her father and her mother Mary (Mo’Nique), and how a teacher, Ms. Rain (Paula Patton), and a social services worker, Mrs. Weiss (Mariah Carey), intervene. Let me say early on that if Lee Daniels and Mo’Nique don’t get Oscar nominations, there is no justice.

As the film opens, Precious is pregnant with her second child and has been suspended from her public school in Harlem. She’s referred to Each One Teach One, an alternative pre-GED program (if that sounds familiar to you, yes, the film uses a program of the Syracuse-based ProLiteracy, an item way at the tail end of the credits). Despite her own nearly paralyzing fears and her mother’s vigorous encouragement to get on welfare and stay home with her instead, Precious goes to school and, little by little, she and her classmates grow and bond. She also applies for her own welfare, which in this case would open the door to independence from her mother, who’s already running a scam involving Precious’ first child. Precious has her baby and decides to keep him, which provokes a brutal explosion when she tries to take the infant home. Coatless, Precious lands on the nighttime winter streets, narrowly avoiding the television thrown down the stairwell after her. Thanks to Ms. Rain, who pulls in all the chips on her considerable Rolodex file, there’s housing out there for Precious and little Abdul, and – I’m leaving out a lot here – Precious has a chance to decisively reject ever going home again.

Like Steven Spielberg’s 1985 screen adaptation of Alice Walker’s novel, The Color Purple, Precious has generated emotional and defensive controversy. Both films contain fathers who rape their daughters, and Precious adds a mother who continues to sexually abuse her daughter after that father has left (besides a dizzying range of other abuses). The harshest criticism so far has come from Armond White of The New York Press weekly in Manhattan. White accuses Daniels and executive co-producers Oprah Winfrey and Tyler Perry – all three have spoken publically about their own childhood abuse – of “pandering and opportunism,” creating a “sociological horror show,” and the most racist depiction of African Americans since Birth of a Nation. On the other hand, commentators like NYU-based journalist Cindy Rodriguez (who wrote for The Post-Standard some years ago), have written astutely and persuasively about how Precious lays out the persistent legacy of slavery and racism that surfaces in the self-worth of many of these characters. Lest we imagine that the 1987 setting safely distances this story, a host of commentary has focused on the present-day plight of similar girls. In the current issue of O Magazine, Winfrey remarks, “I see this girl every day, and I never saw her.”

There’s no doubt the story’s volatile, and even The New York Times’ A.O. Scott, who admires this film, calls it “florid” – which isn’t all that far from “lurid.” But while the subject matter is certainly florid, I want to distinguish that from the way the movie itself is made and talk instead about the film’s restraint. Because in fact Daniels and his cast and crew have refrained from many easy, slapdash things that ruin countless movies by shoving our emotions around. I noticed this first fairly early in the movie – steeling myself at a dramatic moment when I half-expected the music to swell manipulatively and, miraculously, it didn’t. Precious does have a lively soundtrack that’s already out on CD, but Daniels lets his actors do their work.

And what work they do! Besides the principal performances, this makes room for some fine ensemble acting – talk-show host Sherry Shepherd as Cornrows, the school’s receptionist, always on the phone over some boyfriend problem; singer Lenny Kravitz as the vegetarian male nurse whom Precious fixes up with her in one deft comical scene; singer Mariah Carey as the social services worker who anchors the final harrowing scene toward which the movie builds.

In particular, the middle section of the film comprises a series of brief, cleanly written and edited vignettes about Ms. Rain’s classroom itself. These depict time passing as these young women grow and learn and bond in a group setting that is as much therapeutic as educational. Ms. Rain’s interventions can be decisive and dramatic. She stops a fight after a girl sneers at Precious that “F is for fat” (dispensing a lesson in justice about which infraction is really more injurious, she throws the other girl out). But they’re also frequently delicate and nuanced, supremely appreciative of the smallest of victories. Girls who begin the class in stylized poses of indifference and surly defiance gradually discover their own curiosity and even affection for one another. Their participation becomes actively supportive, despite lapses and outbursts, even on the day when Ms. Rain tells them that “the oldest is in charge” and thus the Bahamian immigrant Ramona (a wonderful Chynna Laine) teaches the class.

So when Precious blurts out that she’s just learned she’s HIV+, the group has so progressed that the others can be still and listen – even the jittery girl who started out greeting every remotely serious topic with wild, derisive laughter. It’s worth noting that Daniels and his screenwriter have placed this dramatic development structurally so that it serves a purpose other than stereotyping. In a 1987 classroom, announcing an HIV+ diagnosis would be far more unsettling than today, and how the film handles that might serve as a clue to those who are so jittery about what Precious says out loud.

Perhaps the most telling restraint of all is that addiction – the usual kind anyway – is absent from this story. (The most we get is Ms. Rain having a decorous glass or two of holiday wine.) Now this is almost too good to pass up for any pandering filmmaker who’s into easy short-cuts and sensational stereotypes. Leaving out the booze and dope accomplishes several things, however. What intoxicated characters see is exaggerated, and allows audiences to view the way circumstances are portrayed as distorted. Instead, the film regards the landscape of Precious’ world – well, soberly, without any mind-altering chemical boost. Without that distraction, we see what else is really there. Paradoxically, this makes way to see the full range and force of the fantasies that both Precious and her mother engage in. These include dissociative moments common among those surviving and escaping trauma, fierce schoolgirl daydreams about fitting in and being popular and “looking right,” one intriguingly droll scene in which Precious imagines herself inside a TV screening of the Sophia Loren World War II epic Two Women (which I think precludes the quick, wry sense of humor she starts to display later), and her mother’s more extreme habit of zoning out before the TV that probably verges on the psychotic.

Her mother’s path is, after all, one that Precious could have taken. We see how this all could have happened, and where it might've wound up, most vividly in that final scene in Mrs. Weiss’ cubicle during Mary’s last bid to get Precious back. She’s lucky and so are we. And Mo’Nique has a whole lot more under her hat than “Skinny Women Are Evil.”

* * *

This review is part of the November 25, 2009 issue of the Syracuse City Eagle. “Precious” is playing at both Manlius Art Cinema and Carousel Mall Regal Theaters, and Lee Daniels’ first film, “Shadowboxer” (2005) is available for Instant Viewing or regular rental at Netflix. “Make it Snappy” is a regular film review column. Nancy is a member of the national Women Film Critics Circle.